Education and Chicano Liberation

By Marla G. López

Chicana/o Students

During the civil rights period, many groups saw education as a way to liberate and redefine their places within American society. These were also elements of motivation found in the Chicana/o movement.

In Texas, the demand for space in academic study and increased educational opportunities for Chicana/os posed a challenge to the image of Texas and in turn the United States. The history of discrimination and exploitation within the state created a unique circumstance for its Chicana/o communities – one that was often in the background of the main Chicano movement states such as California and New Mexico. This research explores the journey of UT’s Chicana/o student activism, and how their activism for education grew out of that unique Texas experience and also sought to change it for themselves.

At the University of Texas, students of the Mexican American Student Organization (MASO) and later the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) took up that struggle. Beginning with MASO in 1969, a set of 10 recommendations for the University were sent to the Daily Texan. These demands included substantial academic and financial support for Mexican Americans, a center for East Austin community outreach, a Human Relations Council that included the Afro-Americans for Black Liberation organization (AABL), relegated space within the Daily Texan, and the creation of a Mexican-American center along with a degree and studies program. These would enable substantial systemic change for the benefit of Chicana/os as well as other minority groups.

These demands reflected the wide variety of issues Mexican-Americans had faced in throughout Texas and now at the state’s premier university. For instance, the need to recommend a council of students of specific minority backgrounds demonstrated that the University administrative process had not considered the needs of its most downtrodden students. This can be further understood with the demand for space within the Daily Texan explicitly for Mexican-American students – their voices and needs were not heard, and not many spaces were available for students to find community or engage with the issues that affected them most. These recommendations were to address systemic discrimination and failings of education for the Chicana/o population by having the University take concrete measures in helping Chicana/o students enrolled then and in the future.

These demands were not unlike others previously made at the University. In February of that same year, AABL had published a list of 11 demands. The demands made by MASO were strikingly similar. Key issues and demands such as student housing, student and faculty recruitment, representation, and the establishment of degree programs were among some of the areas students sought action from the University. Through these, it becomes apparent that the climate and focus of the many groups within the student movement were aware of structural racism at the University and society at large. Even more important, they saw that the University was complicit with academic, economic, and social structures that set minority students up for failure or marginalization if it did not take concrete steps to change that or support its students.

Later in 1969, students began forming a MAYO-UT chapter. The Texas-wide organization had seen much progress and political blow back by this time in its efforts to improve public high school education. Having the chapter and consequently the support of major MAYO leaders meant that the Chicano movement at the University had taken a new turn in achieving their goals.

This shift is notable for its reasons and differences in approach and profile. An entry in The Rag by student Fernando D. Gutierrez talks about the seeming difference in approach by both organizations. MAYO had a history of a more radical and militant approach than that of MASO – it was the real deal. In particular, Gutierrez observed the socioeconomic differences among the two, specifically that MAYO was not as middle class in its membership. However, The Rag being an underground leftist news outlet would note this class difference and a lack of revolutionary ideology and action.

Within the organization itself were strategic and leadership issues. Further research led the project to an interview for Texas Christian University’s Civil Rights in Black and Brown oral history project with Amancio Chapa, a UT alum and former MASO and MAYO member. In the interview, Chapa cites how MASO leadership lost focus in their agenda and became satisfied with what could be called ‘token’ positions within student government. This could indicate the class differences among students that influenced their sense of urgency and commitment to the movement’s greater task of liberation for Chicana/os through reformed education.

Though a new and to some a more appealing Chicano organization existed on campus, MASO remained active well into 1970 on campus and with the community such as their protest of fraternity reenactments of battle celebrating Texas Independence and their participation in the Yin Yang conspiracy.

By late spring of 1971, important faculty member Américo Paredes had successfully secured approval from necessary University entities for a Mexican American Studies major similar to that of the Ethnic Studies track. Paredes had been previously appointed to create curriculum for the Mexican American concentration within Ethnic Studies. The Center for Mexican American Studies was also under his supervision. However, by the end of the fall semester, response by University Vice-President Flawn to the Center for Mexican American Studies newsletter El Chisme after it published that the University would then offer a Bachelors of Arts in Mexican American Studies rolled back on all that progress.

A letter in January of 1972 to Dr. Roach, Vice Provost and Dean of Interdisciplinary Programs, Paredes accepted that the newsletter claiming the existence of a B.A. in M.A.S. had mistakenly slipped by faculty review but was alarmed at the fact that Vice-President Flawn went on to state no such thing existed as even a concentration of Mexican American Studies existed within Ethnic Studies at the University. Initially, the University had subjugated Mexican Americans and their histories by placing it underneath Ethnic Studies and thereby upholding euro-centrism and white supremacy in academia. Now, UT had reverted its approval and completely denied the study at the university.

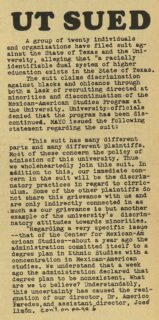

The reversal would not be accepted or taken lightly. MAYO students supported and participated in the ensuing lawsuit against UT and the state of Texas for their discriminatory practices within education. For MAYO, that discrimination was the promise and then revocation of an area of study that represented a key step in changing their historical and future fates within society.

The effort for liberation by Chicana/o students at UT experienced many successes and challenges. The movement saw shared solidarity, organizational shifts, and conflict at the university. Their experiences through this period of the movement reflected the diversity of the Chicana/o student community at UT that would influence and impact the fervor with which they pursued their agendas. Their journey and all they experienced represented the ways in which their efforts to change their lot in life were significantly determined by education and whatever lessons were taught within it. These efforts such as creating more educational opportunity and academic areas of study challenge status quos of Texas history and the Chicano profile posed a threat to the security of power structures that kept Mexican Americans in subjugation both at UT and Texas at large.

Research for this project was conducted over the Fall semester of 2018 in a history seminar titled “the Civil Rights Movement from a Comparative Perspective” with Dr. Laurie Green. Special thanks to the History Department and the Benson Library staff for their guidance and support throughout the research process.

Marla G. López is a fourth year History student with a minor in Geography and a Bridging Disciplines Program certificate in Public Policy. She involved with Jolt, a nonprofit Texas organization that seeks to politically engage and empower the Latinx community. She enjoys painting and spending time with her dog Luna.