Black Student Culture on a White Campus: The Role of Black Greek Letter Organizations

By Katharina Lutz

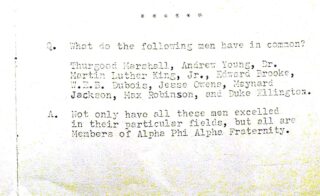

White Greek-letter organizations have been present on American college campuses since 1776 when the first one, Phi Beta Kappa, was founded at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. The first attempts at establishing black Greek-letter organizations, however, were not made until the very beginning of the 20th century, four decades after emancipation. Through education and academic success black intellectuals hoped they could achieve racial uplift. Kappa Alpha Psi, founded in 1911, made it its objective to help more black people successfully enroll at university and improve campus life. But even after the classroom had been desegregated, the rest of the campus including all student organizations were not. Without access to recreational or social activities, black students remained isolated. At times, weeks would go by without black students meeting another on campus, and even if they did the fear of looking clannish persisted. The result was the lack of the very needed academic and psychological support indispensable for African American students trying to navigate the racially charged campus.

How hostile and isolating an environment university campuses and UT’s campus in particular were, becomes evident when scrutinizing the “psychological obstacles at UT” as listed in the newspaper The Austin American-Statesman. Among other racist scenarios, the article addresses the lack of black students (“Walking across the campus with your eyes peeled for another black”, “Realizing that minority recruitment is THE political issue on campus to you”, “hoping the next class will have at least one other black person”), racist staff (“When peer counseling is one black student telling another who are the “redneck” professors”, “Trying to keep your temper when a well-meaning instructor sympathetically asks if you’re a ‘slow learner’”), racist peers (“Feeling hollow inside after passing a crowd of whites and overhearing several off-hand racial slurs”) and their like-minded parents (“Hoping your white roommate’s parents won’t object or create a scene if he or she rooms with a black”). In mentioning that a gathering of young black men would cause campus police “to circle the block an extra time”, it affirms the need for a designated, private space where black students can meet without fear of judgment or even police measures. Black Greek organizations have the potential to fill the void for such a space.

In 1959, three years after the first admissions of black students, black transfer students, former members of APA, created a social club at UT called Alpha Upsilon Tau. According to its charter, its intention was “to promote the general welfare and social security of male students who are and who may later become members of APA, Inc.”The charter stayed all black even though students of all color were allowed under the prerequisite that they were “socially desirable”, “bona fide student[s] at The University of Texas” and “maintained at least a ‘C’ average”. A year later, Alpha Upsilon Tau became an official APA chapter. Walter C. Jones, a founding member of said chapter, summed up the situation at UT at that time as follows: “[T]he university was pretty much segregated. You couldn’t play football; there were no African Americans playing any sports when we first came. Same goes for going to the movies. The only thing that was acceptable for us at that point was the church”

Black women and men were subject to similar experiences and discrimination on campus which is why sororities were created with a similar vision as fraternities. However, female students suffered a twofold discrimination, not only against their race but also their sex. The idea to start a chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority (AKA) at UT was sparked in 1956 when student Mamie Hans Ewing met several professional women who had been AKA sorority members and members of the Beta Psi Omega Austin graduate chapter. As Mamie, like the majority of black women in the 1950s, was a first-generation college student, she had not been aware of these organizations but was eager to found a new chapter in Austin. In 1958, Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Kappa Alpha started actively working on establishing charters at UT, AKA opening theirs in 1959.

The National Panhellenic Council did not recognize African American members as valid until 1966. The newly formed chapters were thus denied membership to the Interfraternity Council or Panhellenic Council and had organized their governing body themselves. Not being part of this umbrella organization only further cemented the gap between white and black Greek letter organizations. This gap showed for example when it came to invitations for white fraternity or sorority parties which generally did not welcome their black counterparts. In 1960, shortly after the APA chapter had been established in Austin, a white sorority which was presumably unaware of the fact that APA was an African American organization invited their members to one of their parties. Knowing they would not be welcome there, the men nevertheless decided to attend the party. According to APA member Carl Huntley, they were ignored for the most part and most white party guests were not willing to talk to them, so after around an hour the Black Greeks decided to leave, content with having made a statement by the mere act of attending. In their opinion getting in touch with white Greek letter organizations, even if provocative as in this case, constituted a step towards better integration.

Black fraternities and sororities also hosted their own events inviting members and black students outside of the Greek organizations alike. These were not only parties, but a variety of cultural contributions which allowed for black students to gather and celebrate their culture. One of them was the support of the Innervisions of Blackness Choir who had one of their gospel concerts in Austin hosted by the Black Greek Council with Alpha Phi Omega members working as ushers. The choir refers directly to its relation to the black experience in its brochure for the event, stating its purpose as educating, emulating, representing and exemplifying the “soul of the black experience through the scope of music”. Its name follows a similar agenda: it tries to evoke “visions of emancipation, citizenship, education, equal employment, sitting in front of the bus, graduating from UT”. The gospel choir does thus not only follow religious goals but is also aware of its social and political reach and responsibility. In supporting other black groups like this choir, e.g. by providing event rooms, staff or financial support, the Greeks contributed to a richer black culture for black students in Austin besides direct political activism.

“It gives you a sense of pride and accomplishment and joy that in some small way you have contributed to something that is still going on and helping to make this even if just in some small way, a better society”, McKinney, who was part of the first generation of APA members in Austin in the early 1960s, sums up the reasons not only him but thousands of other black students decided to join black Greek-letter organizations in Austin and elsewhere, hopeful to improve their situation on their campus.

Katharina Lutz is an exchange student from Würzburg, Germany, majoring in English, French and Educational Sciences. Working on this project over the course of the Fall semester of 2018 for Dr. Laurie Green’s course “The Civil Rights Movement from a Comparative Perspective” allowed her to contribute to the important research on Austin’s rich history and immerse herself in American culture. Special thanks to Dr. Green for offering this insightful class and to the Dolph Briscoe Center of American History for their support navigating the archival material!