The Interplay Between Print Newspapers in 1968

By Patrick Lee

Introduction

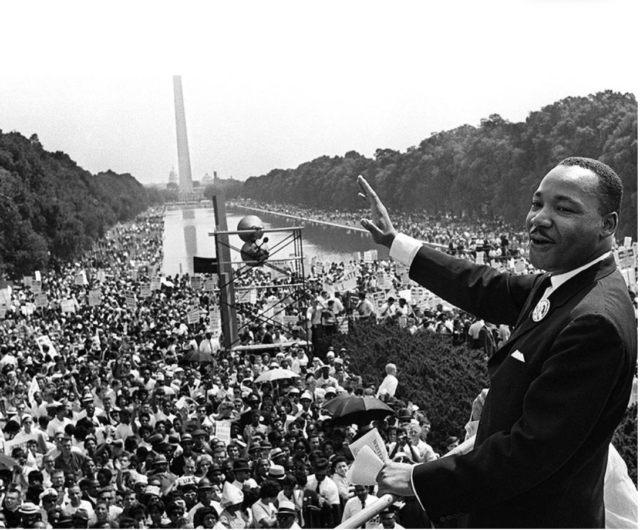

History is punctuated by transformative events with potential to radically restructure its trajectory, from the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 to the Kent State Massacre of 1970. The meaningthat these events come to embody—that is, how these events are signified, how the story unfolds within the national imagery, how one or many narratives emerge—filters through a medium that fundamentally influences how that message is understood and distributed. Mediums take a wide range of forms: print newspaper, television, books, movies, etc. This paper focuses on how a single event in 1968, MLK’s assassination, influenced the way three newspapers operating in The University of Texas competed amongst each other to dictate what the event meant for students and society writ large.

Although difficult to establish a linear cause-effect relationship between the occurrence of an event and the material change that follows, it nonetheless remains important to understand that the strategic way in which an event is framed can generate a national story capable of galvanizing social movements, shifting the dominant discourses, and rescripting the contours of what society qualifies as politically possible. Through the dispersion and digestion of media, society imposes upon its subjects a revaluation of the possible: reprogramming consciousness, subverting traditional paradigms, and expanding novel ideations. Print newspapers epitomized an especially powerful motor of social consciousness and provoker of dialogue during this time since the absence of the internet restricted the scope and scale of digestible media. By printing news and in the process creating a story, language actively dictates, shapes, and infuses meaning within human experiences, inevitably influencing the way people “think about particular objects, events, and situations” (Wenden 2003). As such, even though an undisputable, material reality transpires, language gives coherence to its occurrence by inventing the analytical frame through which one experiences the reality.

Investigative efforts are made here to understand how different newspapers covered a flashpoint event during this time and how their coverage was both uniqueand intertwinedwith certain power structures they were beholden to and world-views they were advocating for. I focus on one historical event with significant resonance: the assassination of Martin Luther King on April 4th, 1968. Coined by literary critic Northrop Frye, “resonance” is the principle by which “a particular statement in a particular context acquires a universal significance” (Postman 1985). This principle extends beyond words and sentences; fictitious characters (e.g. Shakespeare’s Romeo, the paragon of romantic tragedy; DC Comics’ The Joker, a metaphor for unintelligible chaos), objects (e.g. Pandora’s box, symbolizing the curse of curiosity; an olive branch, the metaphor of harmonious peace), and events and places (e.g. Athens, the foundation of rational intellectualism; the Trojan War, and in it the demise that trust precipitates) all contain resonance whereby the original meaning rescripts itself until a universal meaning arises with the power to transcend its original localities and contexts. All mediums of communication contain this capacity for resonating content far beyond its original form. By “direct[ing] us to organize our minds and integrate our experiences of the world,” these mediums are foundational “in the ways we define and regulate our ideas of truth.” MLK’s death was more than rote carbon molecules mechanically rearranging themselves: it contained, within the scale of its vast resonance, an animative narrative that vibrated nationally, evoking compassion and inciting violence, energizing organization, inspiring movements, confirming beliefs while nullifying others, passing civil rights bills. In the struggle between newspapers to inject their respective meanings within the field of resonance and dictate them, one witnesses the power struggle inherent to the process of generating world views.

Historical Context

It was April 5, 1968. In the aftermath of King’s assassination, representations of oncoming ‘black violence’ proliferated throughout the nation which normalized a general state of white panic and anxiety. On the senate floors, President Lyndon B. Johnson politicized the grotesque murder to galvanize Congress into passing the Civil Rights Act of 1968. On the campuses of UT Austin, an official memorial with carefully chosen speakers was quickly sanctioned by the University to mourn King’s legacy. Did this demonstrate the essential goodness and compassion of UT’s Board of Regents? Why did The Austin Statesman sensationalize King’s death as crossing the Rubicon for unfettered black violence? What were the necessary questions asked (or not asked) following King’s death, and what were the implications of the answers for communities, students, and activists at UT? This paper analyzes the resonance of King’s death at UT and how that resonance packaged itself through print media. The paper focuses on the struggles between The Rag(a leftist, ‘underground’ counterculture newspaper), The Daily Texan(a centrist student newspaper tethered to UT’s bureaucracy), and The Austin Statesman(Austin’s comparatively conservative newspaper. For context, it endorsed George W. Bush for president in 2004). It is important to note these organizations vastly differed not only in the politics of what they published, but also in their resource capacity, publishing power, editorial structure, and internal administration. As such, I will first attempt to tentatively outline the philosophical variances that govern each newspaper. Then I will contrast the competing perspectives that dominate each newspaper by parsing through the published articles.

It might appear at first glance that these entities simply represent the natural multiplicity of neutral perspectives, but upon closer examination of the intensity of the papers it is clear that each believed they were fighting amongst each other for high stakes and significant rewards. These rather blatant differences emerge because newspapers have a stake in how they cover an event and, ultimately, in who wins the battle of world-views. Throughout history there are monumental events and flashpoints of conflict that can lead to the domination of one world-view over another and change the course of society, alter public opinion, define culture, catalyze social progress, shape public policy, and ‘write history.’ However, the stakes involved are not only abstract, immaterial victories in social narration; they are also intimately visceral battles within the communities in which these writers eat, breathe, and live. It is important to note that at the time, many students, activists, and ordinary people were fighting for their right to exist peacefully, to eradicate discrimination in education, housing, employment, to free themselves of fighting in a war they didn’t believe in. The stakes were indeed high: as a result of institutional policies, people were left to die, denied equitable opportunities to succeed in life, and discriminated against in every vector of society at a time the civil rights movement was demanding the national installation of justice and equality. Thus, the consequences of reporting an event through a particular framing are not merely macro-societal but are also very much personal and local.

The first issue of The Rag was released on October 10th, 1966, the front-page article written by former Daily Texan editor Kaye Northcott openly blasting the new editor John Economidy as a conservative bigot beholden to the campus police, a proud misogynist, an enemy of leftist politics, and a pro-Vietnam war hawk (Northcott 1966). In this way The Rag emerged as an organic alternative to The Daily Texan, an institution perceived by leftists as a mere “mouthpiece for the university’s information service.” The nature of its origin differs from the Texanand the Statesman, both of which were born out of institutional capital. In a way unseen in Austin newspapers, The Rag actively embraced a philosophy of non-objectivity, an inversion of the normalized expectation that news should reiterate the truth of things in an unbiased, impartial manner. Readers knew The Rag intentionally distilled its content through “anti-establishment and anti-capitalist” frameworks of reasoning and writers never attempted to disguise this reality but made every attempt to openly explain why they held them. The paper eschewed objectivity as a farcical fantasy, explained seemingly innocuous events through broader contexts of power relations and systematic violence, and in this way built the capacity to become a mouthpiece for the changing cultural dynamics. They disavowed the idea of politics as spectatorship and “not only wrote about the news,” but actively made the news: Writers and editors would “organize a demonstration…be at the demonstration…and come back and write about the demonstration.” Politics was not an abstract ideal but rather a participatory game with consequences for the maturation of culture and the distribution of power (Jones 1970).

Another realm The Rag drastically differed from the two newspapers was in its resource capacity. The paper first hit the streets in October of 1966 as the sixth member of the national Underground Press Syndicate. The UPS was an alliance formed not long ago between Free Pressleftist newspapers which included the Berkeley Barb, the Fifth Estate, and others. The UPS network facilitated the distribution of articles and exposure to readership by “interconnecting the papers and giving them a national focus.” The papers were required by membership to allow other UPS members to reprint content from each other without permission or compensation. Within The Rag offices at the University of Texas, the staff comprised of volunteer writers, editors, researchers, activists, sellers, and many times the same people would volunteer to perform multiple roles. These volunteers were often members of other leftist student organizations, most notably Students for a Democratic Society, which provided The Rag with broader personnel and organizational capacity (Dreyer). This lack of institutional backing wasn’t without its struggles and on many occasions The Ragfound itself at odds with the University’s demands. The University suspended students working at The Rag, attempted to censor the selling of articles on campus by arbitrarily enforcing ‘commercial solicitation’ laws, and sued The Rag in 1970 to prohibit the selling of papers on campus (Vizard 1968). Despite institutional resistance, The Rag amassed a substantial readership and over its lifespan demonstrated its publishing power, becoming the most popular underground press nationally while simultaneously “focusing on local politics, covering Austin city government, labor, neighborhood protests, the environment, the developing gay liberation consciousness.” Its internal makeup was radically subversive of traditional administrative norms that had come to define established newspapers. Due to the circumstances of its conception and its unique position as an underground newspaper to directly emerge out of a counterculture community, The Rag was one of first papers to eschew the hierarchical top-down editorial structure deployed by institutional newspapers like The Texan and coined themselves as a “miracle of functioning anarchy,” an anarchy in that roles were volunteer oriented, editorial work was rotational and open to revision, organization decisions were made through a participatory democracy, and there was no static chain of command or institutional obligation (Dreyer). The Ragsought to design itself as an experimental microcosm of the principles it espoused such as participatory democracy and synthesis of politics and culture.

Competing Perspectives

After King was assassinated on the evening of April 4, 1968, there emerged a regional competition in Austin to fill in the narrative vacuum for what exactly King’s death meant for black civil rights, the oncoming summer, and more broadly the future of America. The clashes between representational differences inherent in the three newspapers exposed the conflicting politics of their world-views.

The Daily Texan’s lead page contained 2 articles: the first, an interview series with UT’s “negro students,” “most” of whom “felt violent repercussions would follow the assassination.” Students were quoted as saying: “I feel panicky. The people who believed in non-violence will turn to violence” and “the leaders…are militant. He was the only thing that was keeping the people peaceful.” Another expressed fear that “He was holding the black masses together,” and another claimed negros “will give them [white communities] what they expect” (Oppel 1968).Two conscious editorial choices are noteworthy here. First, the decision to exclusively interview ‘negro’ students, as if by virtue of their black skin they commanded a closer proximity to the truth. Second, in the process of screening which interviews to include or exclude in the final article, there exists a clear consensus in favor of the world-view that King’s death will represent a justification for violent black vengeance. Whether or not this article reflects the total thought processes of black (or any other race) students at UT is irrelevant – it is the active editorial choice to include certain interviews and bury others that results in the cumulative atmosphere of panic and fear. The significant argument purported by The Daily Texanhere was that King was perceived not only by white people, but also by black students, as the last line of defense, a final bulwark separating civil America from a summer of black terror. Within the interview, this ritual of mourning functioned not to re-energize King’s lived principles but rather to relegate his

legacy to that of a mere ‘peace keeper’ of unadulterated black rage quietly keeping the dogs at bay. This framing of King as a neutered peace symbol functionally sanitized other significant components of King’s identity, such as his role as an avid socialist, a law-breaking protestor, an uncompromising advocate of disobeying unjust laws, a ruthless critic of class disparity, poverty, and systematic anti-black racism. The ultimate tragedy was framed as not the murderous loss of a civil rights leader, but instead in how his death emboldened the possibility of black militancy.

The taken-for-granted assumption within these predictions of black violence was that black people were always already eagerly violent but temporarily satiated by the philosophy of a single man.

The Daily Texan’s second article was a fact-based run down on the ‘here’s what we know’ of King’s death: tags like “police find rifle” and “chauffer sees man” that suggested objective reporting were promptly followed with animative yet vague commentaries such as “hostility erupts,” citing “several fire bombings…vandalism…bomb threat[s]” (Associated Press 1968). It remained unstated whether or not these events formed causal relationships to King’s death; it was merely hinted at. Unstated was whether or not these instances of violence were performed by black people; it was merely gestured towards. By immediately sequencing a fact-focused report with vague insinuations towards black violence, it was plausible that readers could form mental associations between King’s death and black violence, even absent a proven connection. Any semblance of objective truth surrendered itself to the racialized yet seductive tale of black virulence spreading all over the nation. The article continues, quoting the perspectives of two powerful politicians. Governor Ellington of Tennessee reassured “the state was taking necessary steps to prevent disorder,” and Governor Connolly of Texas reminisced that although MLK “contributed much to the chaos…in this country…he did not deserve this fate…many of us violently disagreed with him, but none of us would have wished him that fate” (Associated Press 1968). Ellington’s assertion of the state as a positive enforcer of order amidst the newfound chaos reiterates a paternalistic mode of statecraft whereby the benevolent state dutifully contains black violence that would otherwise destabilize social peace. Accordingly, black grievances were framed as synonymous with chaos with no further intellectual efforts made or questions asked to try to understand why it was that chaotic black grievances arose in the first place. Connolly did not explain the subject of his “violent disagreement” against King. What could the two figures possibly disagree over? Perhaps over whether or not black people deserved equal civil rights? Or whether civil disobedience was an effective political stratagem for black liberation? It is unlikely to be the latter. This strain of sentiment was popular during the time—the idea that although you might’ve disagreed with King’s marches towards equality, vehemently opposed black civil rights and supported systematically racist policies and world-views, you wouldn’t kill the guy: a quintessential instance of what Theoharis would call “polite racism.” Polite in the sense that racism is performed under a veneer of goodness, civility, and respectability and racist ideations circulate not with fists but through cloaked rhetoric, electoral politics and explanations of inequality through the lens of cultural and moral failures (Theoharis 2018).

The Austin Statesmen’s lead article was titled “Killing sparks violence: police press manhunt for king’s assassination.” It begins by announcing “authorities” quickly pressed a manhunt to find the killer, whose “assassination touched off negro violence…in American cities and brought a national outpouring of grief.” The article proclaimed, “President Johnson led the nation in mourning” and quickly followed by noting that directly after King’s death, black “violence flared in Memphis and… Nashville, Newark, Washington, Boston, New York’s Harem…and more than half dozen…towns and cities.” In quick response, Governor Ellington ordered “4000 troops into Memphis” since troops had been on standby there “after a king-led march turned into a riot last week.” The article then trails with a myriad of vivid details over people recounting their close-up visceral experiences of King’s death: “I thought it [the bullet] was a firecracker,” “the bullet exploded in his face,” “he got a straight shot.” The article ends by dreading that in response to the assassination “black power advocate Stokely Carmichael urged negros…to arm themselves with guns and take to the streets in retaliation” and that “he wants black America to kill off the real enemy” because he “blamed president Lyndon B. Johnson and Senator Robert F. Kennedy…along with the rest of the nation’s white population” (Associated

Press 1968).

Many editorial choices in this piece are significant in curating a world-view that emphasizes law and order, fear in the face of chaotic unintelligibility, and abject mourning. First, the manhunt is couched in terms of diligent policemen working tirelessly to uncover justice and capture the evil murderer responsible for King’s death. Policemen are framed as agents of truth, not enforcers of violence. Second, there exists zero analysis of what King’s death means for the future of America aside from the two blatantly cited consequences: the first, an upsurge of negro violence all across America, and the second, a justification for all to suspend action in order to mourn. The vivid illustrations of black violence emanating from King’s death were extensive; the prevalence of fear mongering viscous; and an interpretation of King’s death as an accelerant of violent black militarism very apparent. Additionally, the act of mourning was framed as an end in itself, as if the civil response to King’s death was to endlessly dwell in a state of mourning until it was time to move on, with no lesson learned, no resistance energized, no broader conclusion drawn outside the perpetuity of grief. The decision to provide readers with an opportunity to re-live King’s death through colorful descriptions of “firecrackers” and “explosions” functioned as a medium to achieve emotional catharsis for people to expressing joy, anger, fear, sadness at the event in such a way that was contained, individualized, and private. Finally, the allusions of Stokely Carmichael leading “black America” on a rampage to kill off all white people simultaneously created and confirmed the fear of black violence as legitimate and imminent. If the prime minster of the Black Panthers and the icon of black power was declaring war on the entire white population, it was only a matter of time before violent disarray engulfed the nation.

The Rag’s leading article fronted with Stokey Carmichael, a leader of the Black Panthers, declaring “when white America killed Dr. King last night, she declared war on us” (Dreyer 1968). It is noteworthy that the antecedent ‘White’ precedes the subject ‘America,’ as if the two were inseparable entities. To Stokey, the death of King symbolized a declaration of war on all black people. He continues, linking this declaration to a broader critique of the limits of American liberalism for racial progress and the violence of imperialism:

Liberalism is dead. This society cannot speak to the problems of black people. There are only two possible directions for the future: race war or revolution. Imperialism must be crushed. The system of exploiting human beings to fill the coffers of the lily-white few must be stepped. Not only must the Third World gain self-determination, but the colonies at home—the ghettos, not only black but Mexican-American, Indian, poor white, as well, —must gain economic and political independence.

The Rag’s approach to deciphering the meaning of King’s death began not with hypothetical scenarios for black violence but foregrounded a systematic critique of white America’s incapacity to protect and care for black lives. Stokey condemned the structural limitations of liberalism in redressing antiblackness, focusing less on the facts of the individual assassin (e.g. who he was, what gun he used, where he was last seen) and more on the role that the broader system of white supremacy played in rendering King’s death not an isolated tragedy incurred by a lone deranged man but the natural inevitability for black life within a hostile white society. Rather blatantly, Stokey continues:

When Dr. King was shot, white America freaked out. Not, I would suggest, because a great man was killed. But, because the death of that man meant the culmination of an experiment. Hew many of us who have given up on this country (not on its people) have been told by liberals: “You might be right—but why don’t you try working within the system for a while. If you fail, then I will believe you.” Martin Luther King tried to work within, tried to turn the other cheek, tried to give white America a chance, one last chance, to prove that it could reform itself—that things could be worked out. But white America shot down that last experiment and Black people have taken the lesson to heart[1].

For Stokely, King’s death provided further evidence for the claim that white institutions were incapable of ethically reforming themselves. For activists seeking to elevate the condition of black life through legal channels, this tragic event signified the ultimate futility institutional gradualism. The Ragexpressed the ways in which black appeals to institutions had been repeatedly ignored and how the suffocating circumstances that followed rendered direct action, sometimes militant and perceived as violent, as the only accessible method for change. No matter how much social respect one commanded, however much prominence one gathered and however large a crowd one organized, compromising with white America was a death wish; white governance ultimately controlled the destiny of progress because it was always willing to resort to violence when necessary.

Further extrapolating on the topic of violence, The Ragpointed out the unequal process by which “violence” became an accusation reserved for the black and poor while those with power excused themselves of it entirely. For, while civil politicians were quick to denounce the “violence of the black oppressed masses,” they remained inexplicably silent on the “violence of the oppressors who brutally repressed…urban uprisings and waged…genocidal war against the Vietnamese.” If it is true that the circumstances of white society failed to support black communities, if its emphasis on inhumane segregation, hostility against black life, and administrative labyrinth as the sole form recourse was completely inadequate for black progress, then the violence that inevitably erupted was not senseless, unjustified, or even necessarily violent. It was the dispossessed people resisting a violent society that killed their heroes, imprisoned their friends, exiled their leaders. When those in power deployed thousands of soldiers across the nation to subdue black expressions of discontent, that act represented the true form of violent domination: the top down repression of rebellions against oppression.

The Rag embraced a critical interpretation of the urge to mourn that swept across the nation after King’s death. Although mourning the loss of a great individual was indeed a natural part of the healing process, they heavily critiqued the fixation on mourning as sufficient in and of itself, as if mourning was itself somehow equivalent to political struggle. Funeral services and memorial rallies organized by anti-black institutions were no more than feel-good spectacles:

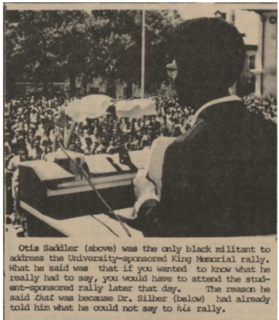

white rituals designed for white people to “exorcise guilt so as not to have to deal personally with these emotions.” A space to pour crocodile tears for those who had refused to support King’s ideals when he was alive and made every effort to resist integration, either through malicious activity or passive complicity, but nonetheless found themselves dealing with throbbing sensations of a guilty conscience in his death. Because although mourning constituted a satisfying form of emotional catharsis, it did not work towards prioritizing or organizing black progress for civil rights: its function for white institutions was not to expand the black struggle but to substitute it entirely with fleeting emotional intensity. On the Friday afternoon of April 5th, 1968, UT organized an official memorial rally in the west mall to celebrate King’s legacy at the same time the Afro-Americans for Black Liberation (AABL) prepared a black-student led march towards the capitol. In this memorial, speakers were carefully chosen to regurgitate truths so obvious and tautological as to not require such incessant repetition. Speakers endless droned on praising King’s Nobel Peace Prize, his dedication to a cause, and how he would have wanted all people to get along (Thiher 1968). What was lacking was any meaningful attempt to explain why America killed this man and what his death meant for the future of black struggle. Within the confines of the Texanand Statesmanworld views, this mourning would have been the end goal, the telos, of King’s legacy.

The stark differences between The Ragand the previous two papers lied in The Rag’sintentional attempts to explain what King’s death signified – what lessons activists should internalize, liberalism’s ceiling for accommodating black struggles, what adjustments to make in organizing for the future – outside the narrow reactionary contexts of black violence and mourning.

Citations

Associated Press. “Snipers Fells Noted Civil Rights Leader Outside Motel, Police Arrests Suspects.” The Daily Texan, April 5, 1968.

Associated Press. “Connally Scores Killing as Act Against Society.” The Daily Texan, April 5, 1968.

Associated Press. “Killing Sparks Violence: Police Press Manhunt for King’s Assassin.” The Austin Statesman, April 5, 1968.

Dreyer, Throne. “Exorcism.” The Rag, April 15, 1968.

Dreyer, Throne. “Rag Mama Rag: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been.” Celebrating The Rag.

Jones, Jeff. “On Objectivity: The Honky Press, The Daily Texan, and The Rag.” The Rag, April 13, 1970.

Northcott, Kaye. “Gen. John Economidy: The First 100 Days.” The Rag, October 10, 1966.

Oppel, William. “Black Students See Troubles Now Nobel Laureate Dead.” The Daily Texan, April 5, 1968.

Postman, Neil, and Andrew Postman. 2005. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Anniversary edition. New York, N.Y., U.S.A: Penguin Books.

Theoharis, Jeanne. 2018. A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press.

Thiher, Gary. “Silber’s Memorial Crisis.” The Rag, April 15, 1968.

Vizard, George. “Ragamuffins Face Fuzz.” The Rag, October 17, 1966.

Wenden, Anita L. 2003. “Achieving a Comprehensive Peace: The Linguistic Factor.” Peace & Change28 (2): 169–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0130.00258.

[1]The two block quotations are in “Exorcism.” By Dreyer