A Watershed Experience: Precursor Sherryl Griffin Bozeman Reflects on Lawsuit to Integrate UT Dorms

The beginning was resolute, certain, almost defiant, a double dare to meet the challenge of insult, flagrant insult, the proverbial salt in the wound of the injustice, dismissive, demeaning sting of racism.

The beginning was resolute, certain, almost defiant, a double dare to meet the challenge of insult, flagrant insult, the proverbial salt in the wound of the injustice, dismissive, demeaning sting of racism.

After many protests and speeches, including sit-ins at Kinsolving Dormitory, our group turned to the courts. The university had stepped up its segregated policies. Black students only could not live in white-only dormitories—which were almost all of the university’s dormitories—they could not even sit in the living room of a for-whites- only dormitory.

There were skeptics, some well-meaning and others, not. Some felt our activities obscured our “purpose” for college, obtaining our degrees. Obstacles, including threats of expulsion were placed before us and consternation from some at our own high schools. None of these obstacles were deterring to me. My resolve, indignation over the racist events and policies, etc. and determination, and ideal of justice and equality made it a no-brainer and impetus for me.

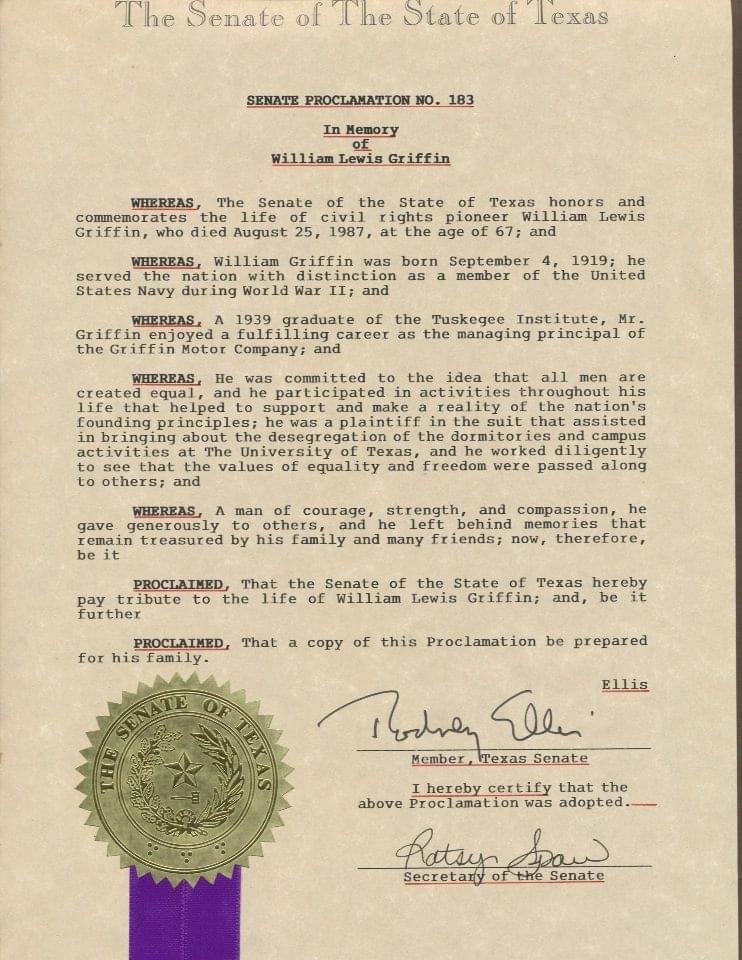

Before the crystallizing of the idea of a class-action suit, when I walked with Maudie and another person to the Kinsolving Dormitory to see what would happen, I was very afraid. What was going to happen? I asked myself. Suppose they called the police, arrested me, or man-handled me or put me out of school right away. However, there were mitigating factors of allies that overruled my fear. Maudie, my schoolmate from Houston’s Worthing High School; mama, who stood up for my decision to go to UT to embrace diversity and opportunity in excellence in education; daddy who gave his permission as I stood in the end of the hallway in Whitis to talk on a pay phone, not only for me to be in the suit, but later for him to be named in the suit since I was under age.

Through a student leader serving as a messenger, Chancellor Harry Ransom had asked me to withdraw, drop the suit in order the create the way for the University to “voluntarily” desegregate its campus housing and other university-owned facilities open to the public and university sponsored student activities including the Longhorn marching band and varsity athletics.

I was asked because the other two plaintiffs were no longer students at the university. I was still a student and about to graduate very shortly. It was a very big decision to make.

Whether the university would keep its word by the chancellor, I considered and weighed positive aspects. I knew it was politically expedient for the university to desegregate because the newly installed President of the United States, Lyndon B. Johnson, was coming to the university to serve as commencement speaker for the spring, 1964 graduation ceremony, my graduation.

I met with the chancellor in his office, and I asked him to put the promise to desegregate remaining segregated aspects of the university in writing. He agreed to do so. Shortly, after our meeting in his office, a messenger hand delivered the typewritten note to me at my dorm. It had the telltale marks such as strikeovers, the sign of a novice typist. I believed that Chancellor Ransom typed the promise himself. Concerning the other uncertainty about the issue of the right thing, I asked myself: Did I want to see as soon as possible and contribute to the results of the university being open to students of all color, with no regard to their race, or be punitive toward the university and exercise a power play? I decided the former and withdrew the suit.

The university kept its word and we as African-American students received a victory by the Board of Regents affirmation on May 15, 1964, days away from my graduation and the day of my birthday. Looking back, I can see God’s hand and providence in the matter. I acknowledge Him and give Him thanks.

Sherryl Griffin Bozeman is a member of the Precursors, a group of African American alumni who share the distinction of being among the first black students to attend and integrate The University of Texas at Austin more than 40 years ago.